Tefillah Part 3 – Fixed Prayer Continued

(Intro Slide) Last week began to look at fixed prayer and its importance in training a believer up to pray effectively, rather than praying at randomly chosen moments of individual inspiration. This week we’ll glean the nature and drive of each prayer and why they correspond to offerings in Temple times. We’ll look at the content that should be covered in each prayer and finish with a look at the siddur, often translated as ‘prayer book,’ but in actuality it means ‘order.’

Women and Fixed Prayer

(Slide) The first thing I want to address is why, according to rabbinic halakha הֲלָכָה, is a woman exempt from fixed prayer. The reasons are many. Torah observance treats the home and synagogue as being co-equal. Some of our most important rituals belong exclusively to the home, such as the Seder, the Sukkah, the Sabbath table, and the Chanukah menorah. The continuity of Torah observance rests on in home more than anything else.

(Slide) It’s a woman’s exclusive role to imbue spirituality into the home. As such, certain mitzvot are set aside especially for women because of their special connection to the home. Family purity laws, candle lighting on Shabbat and holidays, and the separation of challah are rituals that women always observed with particular pride and meticulousness.

(Slide) All societies have recognized that a woman's sensitivity and warmth are ideally suited for motherhood. Moreover, the extraordinary feeling that men can never experience – nurturing a baby inside them – puts women in the position of being the best, most loving caregivers for their children. For the preservation of the family structure, and by extension the overall health of society, the Torah encourages women to embrace this role.

In this vein, the Torah released women from the obligations of certain time-bound mitzvot. This is not because of any difference in the level of sanctity between men and women. Rather, these exemptions allow a woman the ability to be totally devoted to her family without the constraints of having to fulfil such mitzvot at the correct time. Of course, whenever a woman does not face conflicting family obligations, she may fulfil these mitzvot and receive eternal reward. Whatever the case, she is fulfilling Yahweh’s will, who knows that her spiritual growth is intertwined with her primary mission as the family cultivator.

(Slide) Women are obligated to observe all the negative commandments, e.g. don't murder, don't steal. Regarding the time-bound positive commandments, a woman is exempt, with certain exceptions including:

- observance of Shabbat

- eating matzah on Passover

- lighting Chanukah candles

- all the mitzvot of Purim

Women are also required to perform all positive mitzvot that are not time-bound, e.g. mezuzah, returning lost items, etc.

Regarding certain mitzvot, although a woman is technically exempt, women have historically accepted the performance upon themselves. This is the case with hearing the shofar on Rosh Hashana, sitting in the Sukkah on Sukkot, and taking the four species. But this should not come at the expense of family life.

(Slide) When a woman prays, the darkness shudders. In the spiritual realm, a woman starts out as a "heavy mover." This is actually why there is a blessing that men say which thanks the Father for not having made them a woman. The reason is, that a man starts out with less initial potential to navigate the spiritual world and it is for this reason that they are thankful in that they require more constant effort than a woman to achieve perfection. A man is thankful for the requirement to have more labour set before him. On the other hand there is a blessing that a woman says thanking the Father for having made them period.

A woman understands the significance of her more private role. She realises how vital her nurturance is for the survival of mankind. She assumes the role that receives little public recognition, modestly knowing that to Elohim her sacrifices are invaluable.

Eshet Chayil (The Woman of Valour) speaks of the qualities of a woman and no, it’s not about being the happy home-maker. It speaks about the woman being the actual home herself. When a husband is with his wife wherever she is that husband is home. I watched my late grandfather after my grandmother passed away resume life in his home and I tell you he was never home there. I could tell that he felt empty there without her. The Woman of Valour speaks of a woman having wisdom, courage, creativity, even business sense, and having the profound insight to recognise how to relate to individuals according to their specific needs.

For if it wasn't for women mankind would cease to exist.

Fixed Prayer Continued

(Slide) "It is written: 'Man shall not live on bread alone, but on every word that comes from the mouth of Elohim. (Matthew 4:4)'"

(Click) “He humbled you, causing you to hunger and then feeding you with manna, which neither you nor your ancestors had known, to teach you that man does not live on bread alone but on every word that comes from the mouth of Yahweh. (Deuteronomy 8:3)”

What food is to our body, prayer is to our soul. (Click) Rav Yehudah HaLevi wrote that “Man cannot live without food, and similarly our soul, which is Divine in origin, yearns to be connected to the Divine.”

(Slide) Few people will argue that man’s daily physical wellbeing should be centred around three principle times a day to eat - breakfast, lunch and dinner. But man’s existence should not be by this sustenance alone, but by connecting with the Divine at these same times. Everything in the natural is given as a parable for everything in the Spiritual.

(Slide) The Yiddish word for prayer is ‘daven,’ derived from the Aramaic word d'avuhon, which means, "from our fathers" referring to Avraham, Yitzhak and Ya’akov, who first instituted fixed prayer times. We see that the word ‘daven’ also shares the same English root as the word ‘divine.’ So we practice connecting with our Divine source at fixed way-points or pillars in time each day.

So there are two sources as to the origin of our daily fixed prayers. The first is our Patriarchs; each of whom instituted a prayer, which reflected his life experience.

(Slide) Tefillot Shacharit (‘the dawning’ or ‘morning prayers’), which is recited when the sun is rising, reflects the life of Avraham. Faced with many challenges and difficulties as he embarked on the new mission to proclaim the word of Yahweh to an idolatrous world, he emerged triumphant and was treated respectfully by his peers and neighbours.

(Click) Tefillot Minchah (the offering’ or ‘evening prayer’), which recited in the afternoon, when the sun is descending, reflects the circumstances of Yitzhak, who composed it. In comparison with his father, Avraham, his life was one of subtle decline; he never enjoyed the fame or acceptance that his father did. Nevertheless, Yitzhak maintained Avraham’s teachings and continued his legacy.

(Slide) Tefillot Maariv (Evening Prayer), was composed by Ya’akov, whose life was filled with one problem after another, reflected by the dark of night when his prayer is recited. His faith and inspiration during even the darkest times has helped sustain his descendants throughout the “night” of our history, including the past two millennia of dispersion and frequent oppression.

Each one of the patriarch’s prayed all three times, in keeping with the verse “Evening, morning, and noon, I supplicate and moan, and He has heard my voice (Psalms 55:18),” but the life experiences of each was closely identified with a particular time of prayer. The each gave emphasis to their own particular time, meriting their institution and it’s up to us if we want to attempt to maintain this pattern and receive an encounter with the Divine.

Fixed Prayer Aligns with the Daily Temple Offerings

The second source, as we looked at briefly last week, was the daily offerings that were brought in the Beit HaMikdash (Holy Temple).

(Slide) So our three major forefathers received a revelation of the daily offerings that later became codified in the Torah as aקָרְבַּן עוֹלָה korban olah (Burnt offering).The Torah ordains that one lamb was to be offered in the morning and a second lamb in the afternoon. “Offer one lamb in the morning and the other at twilight. (Numbers 28:4)” Though there is no specific offering tied to the maariv prayer, it does correspond to the night time burning on the altar of all the fats and organs left-over from the preceding days offerings. And on Sabbath and Yom Tov, there was brought a mussaf מוּסָף, or additional offering. These brought Israel near to Yahweh and renewed ties with Him. These offerings were never meant to replace prayer, but heighten them. Watching and participating in the ritual slaughter of an animal was meant to fill us with the notion that a very valuable unblemished animal was having its blood shed as a substitute for us. Witnessing such an act, the slaughter of a perfect animal that could have been otherwise used in many practical ways, brought the viewer close. The Hebrew word for ‘offering’ is Korban קָרְבָּן and comes from the root Karov קָרַב, which means “to come close.” Offerings in general would either be felt as a punishment or, if voluntarily brought, would cultivate feelings of love through the giving of oneself to Yahweh.

(Slide) We can learn a lot from this, because many people think of the Temple and post-Temple dispensations only and often view the post Temple period as a time which brought a change in the Torah from animal sacrifices to sacrifices of praise, but if we look at the pre-Temple period we see that this is a type of post-Temple period already in action. In the future we will have another Temple era, but this time without end. So, we have two major non-Temple eras, with sacrifice of praise being sufficient and two major Temple periods with sacrifices in full accompaniment to the offering of praise. Neither negates the other, but sacrifice of praise is constant that’s why we have it mentioned in the TaNaK in Hosea 14:2b “…accept us graciously that we may offer the praise of our lips as sacrificial bulls.” and again in the Netzarim Ketuvim in Hebrews 13:15 “… let us offer the sacrifice of praise to Elohim continually, that is, the fruit of our lips…”

Why are lambs offered up at these three fixed times?

(Slide) Yahshua is our shepherd and by offering of two lambs daily, we proclaim that he leads us morning and evening, through all the different periods in our lives. We no longer have a Temple, but we saw (last week) that according to 1 Corinthians 6 that each person is considered a miniature Temple

(Slide) “Do you not know that your bodies are temples of the Ruach HaKodesh, who is in you, whom you have received from Elohim? You are not your own (1 Corinthians 6:19)” And this Temple requires timed operation in accordance with the Temple in Jerusalem, which was a reflection of the Heavenly Tabernacle. And this operation consists of the constant fruit of our lips according to Hosea 14.2b. This gives us deeper insight as to why we read (Click) “Rejoice always; pray without ceasing; in everything give thanks; for this is Elohim’s will for you in Yahshua HaMoshiach. (1 Thessalonians 5:16)” And we noted that this process was not limited to non-Temple times, but was also the central feature of the Korban. If the offering of an innocent unblemished animal was not enough to elicit a change in self, then the soul and conscience of a person is considered pretty seared and the Korban is ineffectual and reduced to a legalistic act.

Shacharit

(Slide) Okay, the first fixed prayer is Tefillot Shacharit (dawn prayers) can be likened to climbing up and back down a ladder. We ascend to the heavenly spheres and fortify our sensitivity for Yahweh and His will. After this daily booster we descend, equipped to tackle the day and the struggles it will present.

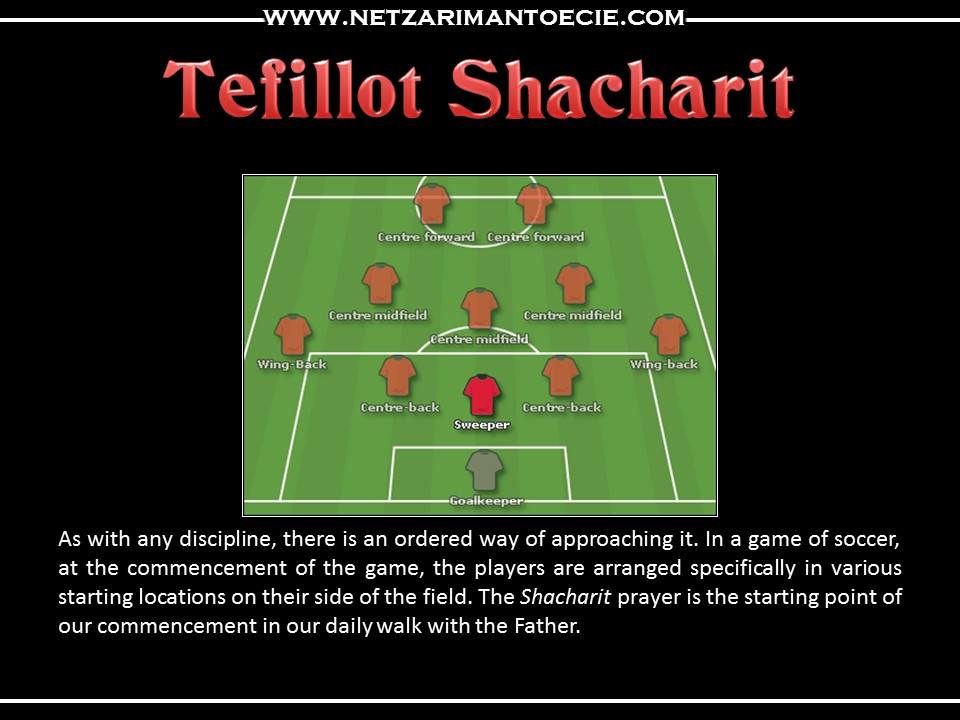

(Slide) As with any discipline, there is an ordered way of approaching it. In a game of soccer, at the commencement of the game, the players are arranged specifically in various starting locations on their side of the field. The Shacharit prayer is the starting point of our commencement in our daily walk with the Father. This prayer is led into by a style of morning conduct, which is best suited at executing the day. Firstly, there is a range of things set in place before its even commenced. We arise in the morning thanking Yahweh for awakening us with a renewed soul. We then wash and relieve ourselves and prepare everything we need to pray Shacharit.

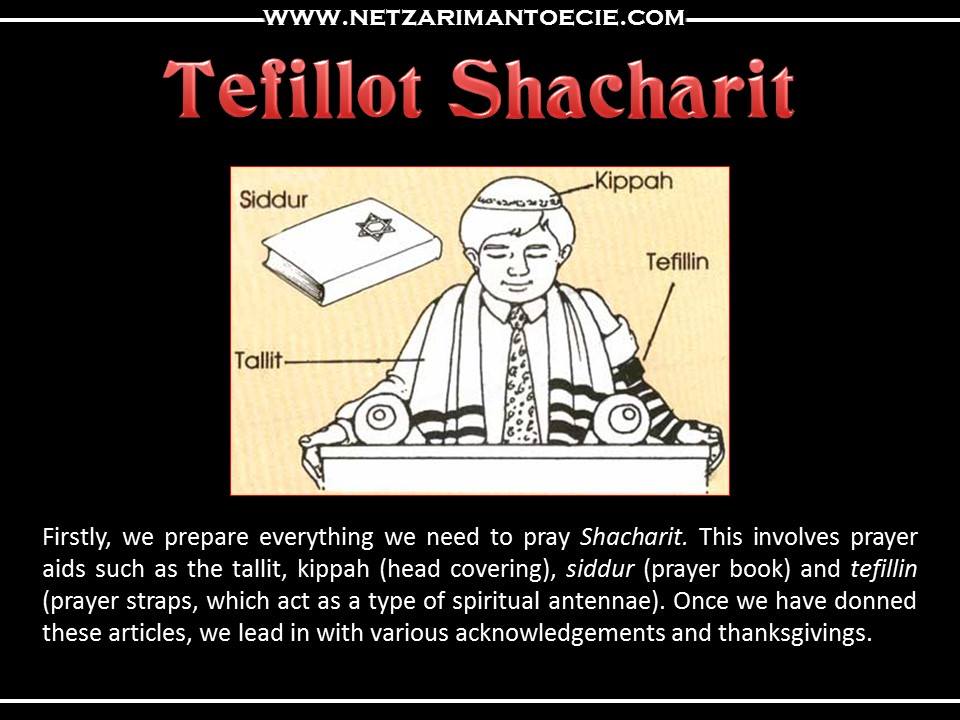

(Slide) This involves prayer aids such as the tallit, kippah (head covering) siddur (prayer book) and tefillin (prayer straps, which act as a type of spiritual antennae). Once we have donned these articles, we lead in with various acknowledgements and thanksgivings.

(Slide) Shacharit can be observed anytime between sunrise and midday (the earlier the better). The prayer should last at least half an hour, especially if you are involved in leadership or mentoring roles within the body of Moshiach.

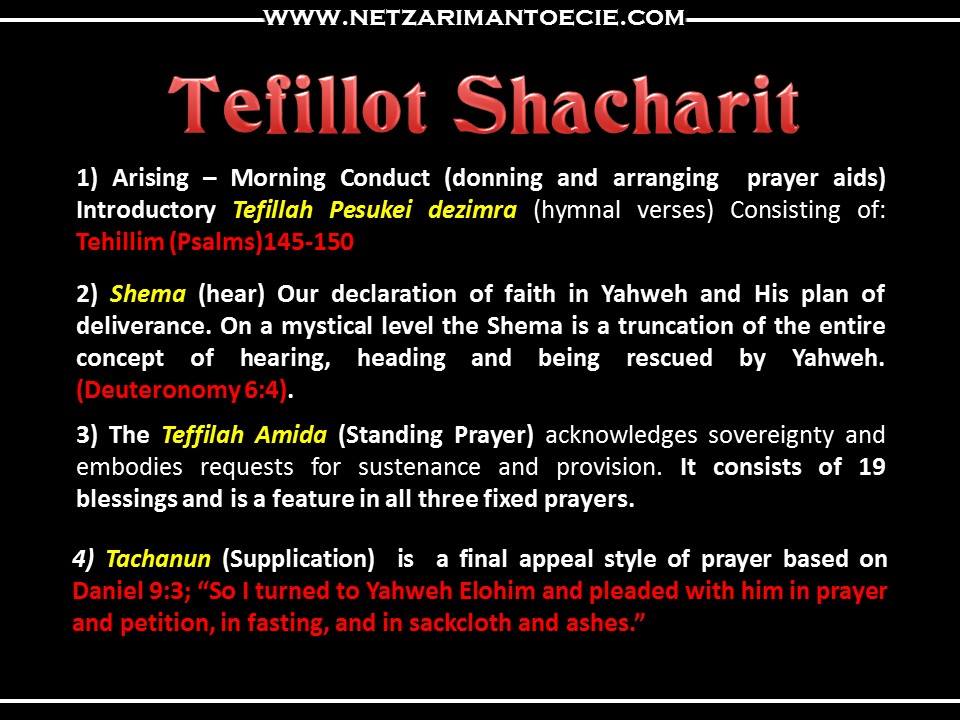

The warm-up is the morning blessings, the highpoint is the Shema (our declaration of faith), and the conclusion consists of confession based prayer, acknowledging any of our inadequacies and short comings.

(Slide)Read off Slide

In conclusion, fixed prayer binds a person to Yahweh, whether he feels inspired or not and when he does feel inspired, his fixed prayer schedule lifts spontaneous prayer to greater heights.

So today, we looked at a woman’s role in prayer, the origin of the three fixed daily prayers, their relation to offerings, and their unique emphasises. We looked at the need for fixed prayer a little bit more and the key features of the first fixed prayer – Shacharit.

Got Questions? ask in the comments below.

PDF Downloads

Video Teaching

Segment 1

Segment 2

Audio Download

Study Notes and Slides

Tefillah Part 2

Concentration & Fixed Prayer

Introduction

Last week we looked at the subject of prayer from a uniquely Scriptural perspective and we found out that it’s an act that is undertaken to a greater or lesser extent by every human being. (Slide) From the most primitive to the most sophisticated, from the most wicked to the most righteous, from the most religious to the most non-religious, for the most significant or insignificant of reasons, prayer is undertaken in a countless multitude of ways by everybody. Everybody prays. So this subject is not foreign to anyone, even the unbeliever and the atheist has some core knowledge of the concept of prayer and secretly they’ve all attempted it.

(Slide) Adolf Hitler prayed. In fact, he would sometimes spontaneously pray during his speeches. Few world leaders would even think about doing this during a speech. Every enemy of Israel had a religion and therefore every foe of Israel prayed. Pharaoh prayed, Haman prayed, Goliath prayed, Nebuchadnezzar prayed, even Cain prayed.

A person who prays is no more righteous than a person who says thank you to a waiter who arrives with their meal! It depends who you pray to and what your motives are. But prayer is the most misunderstood and lightly treated activity in the world. Most people underestimate prayer’s full potential.

(Slide) We looked at how prayer is defined in Western thinking as a purely supplicatory act, taking on the form of petitioning, pleading, begging, imploring, beseeching and even demanding. It is from this narrow view that it receives the word ‘prayer’ derived from the Latin word ‘precor’,’ meaning to ‘beg’ or ‘supplicate.’ No doubt, such a term is given for this act by the Greco-Roman mindset because of its outward appearance, which often takes on various degrees of this definition. But the true definition of prayer from a purely Hebraic perspective describes the inner workings of prayer rather than the outer workings, carrying the name ‘tefillah,’ which means ‘to self-analyze with a view of closing down any distance between a man and his Creator.’ Tefilah shares its root with yefalel, which means “judgment,” and with pallel, which means to “judge.” To pray (lehitpalel) is to judge oneself.

(Slide) So one should practice prayer with a view to receive a change of self, rather than to project change onto the Almighty. What sort of change of self did we talk about? A change of heart. We found that this takes work called in Hebrew ‘avodah,’ which means ‘service’ or ‘labour.’ This concept is derived from Deuteronomy 11. “And it will be, if you hearken to My commandments that I command you this day to love Adonai, your Elohim, and to serve Him with all your heart and with all your soul (Deuteronomy 11:13)”

Prayer Takes Work

This type of avodah is called ‘service of the heart’ (avodah shebalev), which is the process of awakening the hidden love within the heart until a state of intimate union with the divine is achieved (I.e., embarking on achieving oneness within to draw oneness down from above). For example a person who prays by saying one thing and thinking something else shows division within his own being. Yahweh discerns thoughts as equally efficiently as he discerns words, so a mixed message is heard whenever one prays aloud saying one thing and simultaneously thinking something else. The mouth is there but the heart isn’t. It is better to pray with the mouth lacking than the heart lacking. (Slide) With such a type of prayer “the Ruach HaKodesh prays for us with groaning that cannot be expressed in words. (Romans 8:26b)”

“And when you pray, do not keep on (with) βατταλογέω battalogeo (idle words) ἐθνικός ethinkos ([which is] savouring to the nature of heathens), for they think they will be heard because of their many words. (Matthew 6:7)” The type of idle words referred to here is a multitude of speech without substance behind it. The workings of the heart should come out through the mouth. (Click) “The good person out of the good treasure of his heart produces good, and the evil person out of his evil treasure produces evil, for out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks. (Luke 6:45)”

The Value of Concentration

(Slide) So if one employs avodah shebalev (service of the heart) when entering into tefillah then he achieves kavannah, (commonly translated as ‘concentration’) the chief component of successful prayer. At this point we must bear in mind that successful prayer isn’t defined by receiving the object of a request but rather making a connection with the Father and feeling that connection, everything else in prayer is secondary. Failing to produce kavannah is the primary reason prayers by most people (at whatever level of standing before the Creator) miss the mark. (Click) “But the witless can no more become wise than a wild donkey's colt can be born human. Yet if you devote your heart to Him and stretch out your hands to him…and not let unrighteousness near your tents…there will be no defect; and you will be firm and free from fear. (Job 11:12-13,14,15)” On a deeper level, we found that kavannah means ‘preparedness,’ or ‘direction,’ as in the sense of the Hebrew word, kiven, which means ‘to aim.’ Kav (כַּו) also literally means “window” (Book of Daniel 6:11[10]). (Slide) “With the right intention and focus we have the ability to open a window to our soul—our deepest self—and allow this internal, authentic self to be expressed and experienced.” – (Rav Pinson Dovber)

(Click) When one prays with intense kavannah it becomes his identity. “In return for my friendship they accuse me, but I am prayer. (Psalm 109:4)” Because David always prayed he became like a living prayer – (Rashi)

To have the best chance of praying with kavannah we need to eliminate distraction before praying. Turn the TV, radio and mobile phone off. Pray in a place where you’re least likely to be disturbed. Prayer is all in the preparation. If you prepare yourself before prayer, by clearing the mind and emptying it of worries and frivolous thoughts you’ll have the best opportunity to make the connection. (Click) “In the morning, Yahweh, you hear my voice; in the morning I arrange my requests before you and wait expectantly. (Psalm 5:3)”

Where to Pray

The best place to pray is a place of worship, a shul or synagogue. According to the Talmud (Megilah 29a) the synagogue is a “miniature temple,” and thus a perfect place for tefillah. This is because such a place is dedicated for this purpose. A place of worship, prayer and study will instinctively evoke a desire to prayer. It is for this reason that we also pick a specific place to pray in our homes. “This reserved space will become our sacred space, and the moment we enter it, we will feel charged for prayer.” – (Rav Pinson Dovber)

Whatever the case, prayer is best done in a place of solitude. (Slide) “But when you pray, go into your tameion ταμεῖον (private chamber), close the door and pray to your Father, who is unseen. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you. (Matthew 6:6)” “But Yahshua often withdrew to lonely places and prayed. (Luke 5:16)” “After sending (his disciples) home, he went up into the hills by himself to pray. Night fell while he was there alone. (Matthew 14:22)”

Prayer is private. Even when we pray as a congregation we don’t make a show of or parade our prayer before others. (Slide) "And when you pray, do not be like the hypocrites, for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and on the street corners to be seen by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. (Matthew 6:5)”

We looked at the type of things required to achieve powerful tefillah. (Slide) Righteous living, because, “The prayer of a righteous person is powerful and effective. (James 5:16)” (Click) We looked at asking with the right motives. “When you ask, you do not receive, because you ask with wrong motives, that you may spend what you get on your pleasures. (James 4:30)” (Click) We looked at praying in Yahshua’s name. “You may ask me for anything in my name, and I will do it. (John 14:14)” “Very truly I tell you, my Father will give you whatever you ask in my name. Until now you have not asked for anything in my name. Ask and you will receive, and your joy will be complete. (John 16:23b-24)” (Click) We learnt to wait. “Whoever is patient has great understanding, but one who is quick-tempered displays folly. (Proverbs 14:29)” “Better a patient person than a warrior, one with self-control than one who takes a city. (Proverbs 16:32)”

So we looked at tefillah (self-analysis), avodah (service) and kavannah (direction). The specific type of service and direction we looked at was avodah shabelev and kavannah shabalev (the ‘service of the heart’ and the ‘direction of the heart’).

Ritual, Formal or Fixed Prayer

Now we’ll be looking at when to pray. The short answer: As much as possible. But uniquely, we are obligated to pray at least three times a day. Again, we have an apparent anomaly, like finding the elusive commandment to pray, there appears to be no direction to observe a custom of praying three times a day in the Torah. King David said, (Slide) “But as for me, my prayer is to you, O Yahweh. At an acceptable time, O Elohim, in the abundance of your steadfast love answer me in your saving faithfulness. (Psalm 69:13)”

“Evening, morning and noon I cry out in distress, and he hears my voice. (Psalm 55:17)”

Many people today do not see the need for regular, formal prayer. "I pray when I feel inspired to, when it is meaningful to me," they say. A full walk before Elohim isn’t one marked by waiting around for moments of inspiration. We have to stir up inspiration. The attitude to pray when inspiration comes alone overlooks the need to practice prayer.

If we want to do something well, we have to practice it continually, even when you don't feel like doing it. This is as true of prayer as it is of playing a sport, playing a musical instrument, or writing. The sense of humility and awe of Yahweh that is essential to proper prayer does not come easily to modern man, and will not simply come to you when you feel the need to pray. If you wait until inspiration strikes, you will not have the skills you need to pray effectively. If you don’t set fixed times for prayer, you will rarely find a desire to pray and then if you do, prayer will be difficult. If we pray beyond times of hardship and great rejoicing, we will learn how to express ourselves properly in prayer.

The prophet Denial prayed at fixed times. (Slide) “Now when Daniel learned that the decree had been published, he went home to his upstairs room where the windows opened toward Jerusalem. Three times a day he got down on his knees and prayed, giving thanks to his Elohim, just as he had done before. (Daniel 6:10)”

The early Apostles prayed at fixed times. (Slide) “One day Kepha and Yochannan were going up to the Temple at the time of prayer—at three in the afternoon. (Acts 3:1)”

But where do these regular fixed times of prayer appear in the Torah?

(Slide) Avraham was the first to pray the Morning Prayer (shacharit, שחר meaning “the dawning”). “Early the next morning Avraham got up and returned to the place where he had stood before the Yahweh (Genesis 19:27)” Shacharit corresponds to the daily morning Korban sacrifice offered in the Bet Hamikdash (Holy Temple);

(Slide) Yitzhak was the first to pray the Afternoon Prayer (minchah, מִנְחָה meaning ‘the offering’ corresponding to the daily offering in the Temple which occurred in the afternoon) “He went out to the field one evening to suwach שׂוּחַ (manifest), and as he looked up, he saw camels approaching.(Genesis 24:63)” Mincha corresponds to the afternoon daily Korban (offering) in the Beit Hamikdash;

(Slide) And Ya’akov was the first to pray the evening prayer (maariv, מַעֲרִיב meaning “evening”) “When he reached a certain place, he stopped for the night because the sun had set. Taking one of the stones there, he put it under his head and lay down to sleep (Genesis 28:11)” After seeing the vision of the stairway to heaven he awakens and promptly prays. Maariv corresponds to the daily evening Korban (offering) in the Beit Hamikdash.

In the Zohar (where the inner meaning of the Torah is revealed) it is explains that each of the three Patriarchs represented a particular quality which they introduced into the service of Elohim. Avraham served Yahweh with love; Yitzhack—with awe; Ya’akov—with mercy. Not that each lacked the qualities of the others, but each had a particular quality which was more in evidence. Thus Avraham distinguished himself especially in the quality of kindness (חסד) and love (אהבה), while Yitzhack excelled especially in the quality of strict justice (דין) and reverence (יראה), while Ya’akov inherited both these qualities, bringing out a new quality which combined the first two into the well-balanced and lasting quality of truth (אמת) and mercy (רחמים). We, the children of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, have inherited all these three great qualities of our Patriarchs, and this enables us to serve Yahweh and pray to Him with love and fear (awe) and mercy.

(Slide) So we see that the three daily prayer services were instituted in accordance with the daily sacrifices of the Temple period. This is because each person is a living Beit Hamikdash. “Do you not know that your bodies are temples of the Ruach HaKodesh, who is in you, whom you have received from Elohim? You are not your own (1 Corinthians 6:19)” “But the temple (Yahshua) had spoken of was his body. (John 2:21)”

(Slide) This is what it means when we read, “Bring a prepared speech with you as you return to Yahweh. Say to him: "Completely forgive our iniquity; accept us graciously that we may offer the praise of our lips as sacrificial bulls. (Hosea 14:2)” Like the Temple, we take on three key rectification services throughout the day, using our mouths as accompaniment or substitute for the offering of animals. Again in Hebrews we have a similar reference; “By him therefore let us offer the sacrifice of praise to Elohim continually, that is, the fruit of our lips giving thanks to His Name. (Hebrews 13:15)” Many interpret this as being a teaching that replaces animal sacrifices, but Hoshea, a book of the TaNaK, clearly shows us that this was always required, whether it accompanied an actual offering or was done in place of one. So if our bodies are really temples in which dwells the Ruach HaKodesh, we need to align ourselves to the tabniyth תַּבְנִית pattern of the real Temple’s daily function.

In the coming weeks, we’ll look at the different aspects and contents of the three daily prayers, how our Moshiach instructed us to pray and how it lines up with the Shekarit, Mincha and Maariv. We’ll look at the difference between prayer and brachot (blessings). Then we’ll move onto prayer aids, such the tallit (prayer shawl) and phylacteries (straps) commonly known as “tefillin.” We’ll look at the role of Psalms and the role of fasting in prayer. By the end, if you stick with us you’ll be equipped to be a real prayer warrior. Amein

The next thing we have to look at is the unique individual structure of each of the three daily prayers, but before we do this it is important to find out how the content of these prayers came about. Imagine that one hundred and twenty of the greatest computer scientists in the world are brought together and given unlimited access to the most advanced technology available to write a program for a supercomputer designed to remain state-of-the-art for all time. They are joined by visionaries able to discern every possible requirement of the future generations of computer users. This portrayal, if it where it ever possible, is but a glimpse of the extraordinary process that was undertaken the Men of the Great Assembly to compose the structure and each of the three daily tefillot.

Shacharit

Minchah

Maariv