The Role of Hebrew Language in Prayer

This week I want to focus on the role of the Hebrew language in prayer.

The fourth century "church father" Epiphanius gives a detailed description of the early Netsarim in his seminal treaties on various heresies called Panarion (Greek: Πανάριον, "Medicine Chest"), to which 16th-century Latin translations gave the name Adversus Haereses (Latin: "Against Heresies") and he touches on more than several unique observances that characterise Netsarim from Christians (Slide).

But these sectarians... did not call themselves Christians—but "Nazarenes,"... However they are simply complete Jews. They use not only the New Testament but the Old Testament as well, as the Jews do... They have no different ideas, but confess everything exactly as the Law proclaims it and in the Jewish fashion-- except for their belief in Messiah, if you please! For they acknowledge both the resurrection of the dead and the divine creation of all things, and declare that G-d is one, and that his son is Y'shua the Messiah. They are trained to a nicety in Hebrew. For among them the entire Law, the Prophets, and the...Writings... are read in Hebrew, as they surely are by the Jews. They are different from the Jews, and different from Christians, only in the following: They disagree with Jews because they have come to faith in Messiah; but since they are still fettered by the Law—circumcision, the Sabbath, and the rest-- they are not in accord with Christians.... they are nothing but Jews.... (Epiphanius; Panarion 29)

Note that in this extract he points out that these sectarians as he called them were trained to a nicety in Hebrew. This is interesting, because many of those embracing the faith where either Jews of which Hebrew was not their first language and many who were complete foreigners embracing both the Covenant and the Testimony of King Messiah Yahshua according to Isaiah 8:20.

“To the teaching and to the testimony! If they will not speak according to this word, it is because they have no dawn. (Isaiah 8:20)”

Apart from a range of other interesting facts we see from this extract that Hebrew was taught and learned by early Netsarim who were not familiar with the language of the TaNaK.

(Slide) The Talmud states that it is permissible to pray in any language that you can understand; however, traditional Judaism has always stressed the importance of praying in Hebrew. A traditional Chasidic story speaks glowingly of the prayer of an uneducated Jew who wanted to pray but did not speak Hebrew. The man began to recite the only Hebrew he knew: the aleph bet. He recited it over and over again, until a rabbi asked what he was doing. The man told the rabbi, "The Holy One, Blessed is He, knows what is in my heart. I will give Him the letters, and He can put the words together."

(Slide) Today, more and more liberal movements are increasingly recognizing the value of Hebrew prayer. Many years ago, you would never have heard a word of Hebrew in a Reform synagogue. Today, the standard Reform prayer book contains many standard prayers in Hebrew, generally followed by an English translation.

There are many good reasons for praying in Hebrew: It provides a unique link to Jews and other Netsarim all over the world, because it is the language in which the covenant with Elohim was formed and it expresses our desire not to change that which Yahweh has set in motion.

An individual expresses himself most proficiently in his own native tongue and it is therefore considered perfectly legitimate in Judaism to pray in one’s own language insofar as prayer is an act of individual connection and communication with Elohim. The use of Hebrew in prayer moves this act beyond just an INDIVIDUAL connection.

(Slide) A Jew or Netsari when praying is supposed to be taking part in the prayers of the entire people of Israel. So, as we looked at last week, a Torah observant individual prays three times a day, using the same words in the same language, becoming unified in the global chorus of continual prayer that moves across the whole globe. Usually after the Amidah or Netsarim Amidah, personal prayers are entered into and put in the individual’s own language.

On a Kabbalistic level, it is good to pray in Hebrew because Hebrew words are infused with spiritual power, stemming from the idea that Yahweh created the universe by speaking ('Let there be light', etc.)--in Hebrew.

Two of the most important reasons to learn to pray in Hebrew is that it joins and attunes a person to the chorus of bodily prayer, not only as it happens around the globe, but in the heavenly realms as well. And secondly it is the language of creation and of a purely Torah centred mindset.

Any language other than Hebrew is laden down with the connotations of that language's culture and religion. When you translate a Hebrew word, you lose subtle shadings of Jewish ideas and add ideas that are foreign to the Torah. Only in Hebrew can the pure essence of Torah thought be preserved and properly understood.

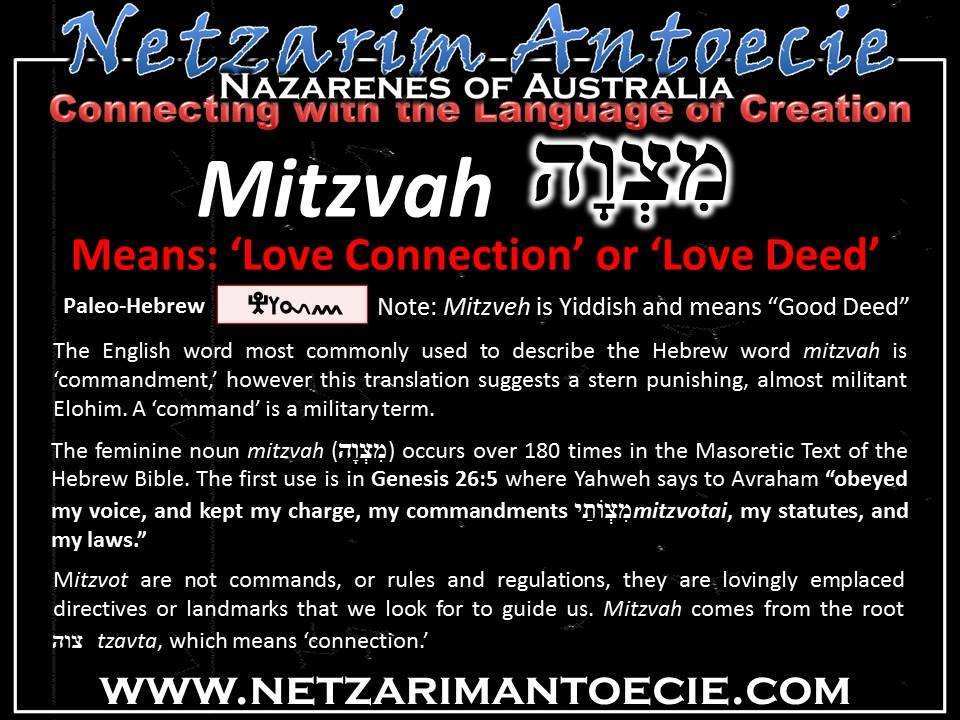

(Slide) For example, the English word "commandment" connotes an order imposed upon us by a stern and punishing Elohim, while the Hebrew word mitzvah, meaning ‘love deed’ implies an honour and privilege given to us, a responsibility that we undertook as part of the covenant we made with Yahweh, a good deed, a love deed that we are eager to perform.

The English word most commonly used to describe the Hebrew word mitzvah is ‘commandment,’ however this translation suggests a stern punishing, almost militant Elohim. A ‘command’ is a military term.

The feminine noun mitzvah (מִצְוָה) occurs over 180 times in the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible. The first use is in Genesis 26:5 where Yahweh says to Avraham "obeyed my voice, and kept my charge, my commandments (מִצְוֹתַי mitzvotai), my statutes, and my laws".

The mitzvot are not commands, or rules and regulations, they are lovingly emplaced directives or landmarks that we look for to guide us.

Learning Lashon Kodesh

For many newly birthed Nazarenes Israelites the Hebrew language looms back at them from the page of their congregation’s Torah scroll like a daunting mystery. Many times I have looked at its fiery shaped letters in utter amazement at how so much meaning and detail can be drawn from such simple yet passionate strokes. Looking carefully at it, even without knowledge of its meaning, can be rewarding as one notices that each individual letter is crowned with its own kippah.

Believers shouldn’t be afraid to learn a bit of Hebrew. Excuses like, “It’s not a salvation issue” or “I’m too old” shatter on rocks for the mind of one who is insatiable for pursuing the original intent of the words of his heavenly Father. Developing an intense desire to do something can be implemented at any age. Last week we looked briefly, at Rabbi Akiva, a former gentile who became one of the most influential commentators on the Torah. Many Jews know the story of how he didn’t start studying Torah until he was forty years of age. How did he make such a huge leap at the age of 40?

(Slide) Akiva was tending flock in the hills of Judah. He became thirsty and went to his favourite brook in the hills to take a drink. As he was drawing the crystal clear water in his palm and putting it to his mouth, something caught his eye. He saw drops of water falling on a huge stone – drip, drop – and directly where the drops were falling there was a deep hole in the stone. Akiva was fascinated. He gazed at the drops and at the stone.

“What mighty power there is in a drop of water,” thought the shepherd. “Could my stony heart ever be softened up that way?”

“Hello, Akiva! What are you gazing at?” It was Rachel, his master’s daughter. She was wise and kind and fair.

“Look what the little drops of water did to the rock,” Akiva exclaimed. “Do you think there is hope for me? Suppose I began to study the Torah, little by little, drop by drop. Do you think my stony heart would soften up?”

“O yes! Akiva. If you persevere, if you keep it up as these drops of water.”

But I am forty years old! Is it not too late to start?”

“O no, Akiva. It is never too late. If you promise to learn our holy Torah, I know you will not be ignorant for long.”

The shepherd gazed at the drops of water for a long time, and then his mind was made up.

And this is how Akiva the shepherd became the great Rabbi Akiva, the greatest and wisest scholar and teacher of his day, who had 24 thousand pupils! He often told them that it was a drop of water that changed his life.

(Slide) A casual reading of Jeremiah 8:8 should be enough to motivate anyone to not take any English translation as a flawless rendering of the original script. The Torah and the entire TaNaK, including most of the ensuing prayers were written in Hebrew. As the saying goes, "there is no such thing as an accurate translation." Even the best translation cannot convey the entire intent of the original.

(Slide) "A translation of the biblical text is a translator's "interpretation" of the text. The translator's beliefs will often influence how the text will be translated and anyone using his translation is seeing it through his eyes rather than the original authors. Only by studying the original language of the Bible can one see the text in its original state." – Learn to Read Biblical Hebrew (Jeff A. Benner)

When one prays in Hebrew, he is assured that he is praying exactly as our prophets and sages intended it.

Approaching Hebrew

A believer who is foreign to the Hebrew language should try and view it as a unique and exquisite code or cipher that contains depths of profound meaning that will unlock a great treasure of understanding. No believer should view it as a redundant language of gobbledygook that is pointless to learn. Viewing Hebrew as a code should stir the heart of the inquisitive child within and spark the same interest as a child who tries feverishly to break the riddle on his secret Batman decoder ring.

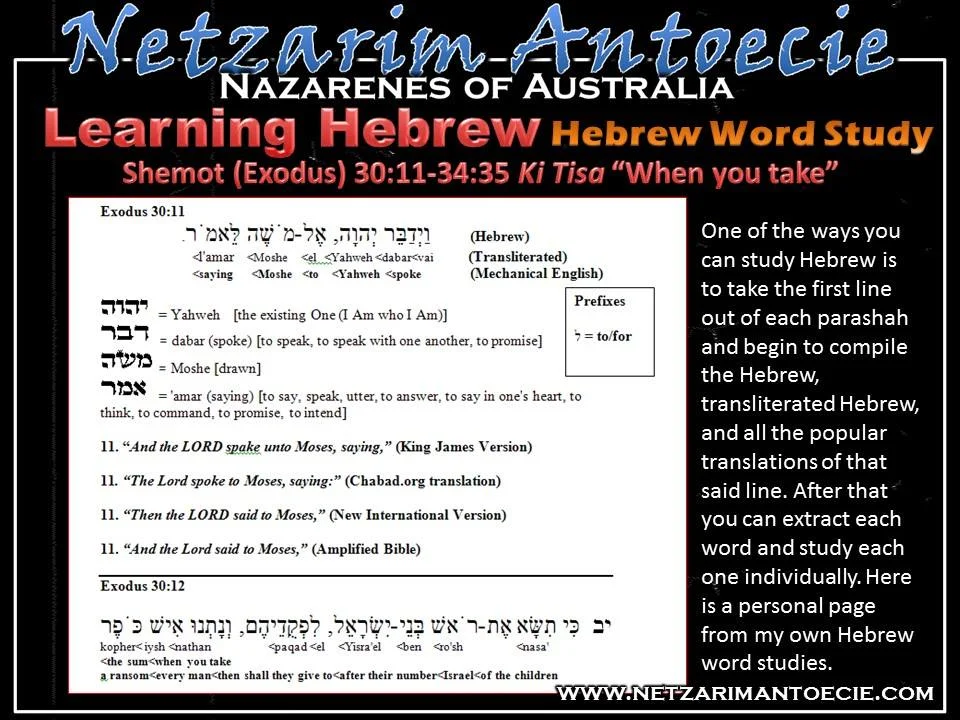

(Slide) Here’s something you can do if you have a Strong’s Concordance and/or Internet access. As a new Torah Portion rolls round for the week find some time and have a look at the first couple of verses for that parashah. Note down a few major translators’ versions of the same verses and go back and look at each Hebrew word. You’ll soon find words within words that amplify meaning to the verse. Sometimes you’ll even see a direct link within one verse to another that is hidden in the translated English. Write the Hebrew words in sequence as you source them and compare them to a popular translation. Along the way you just might pick up a bit of Hebrew to boot whilst studying the week’s parashah at the same time. Keep a record of this as you study a few verses each week and when the next year roles round pick up where you left off with a couple more verses. Before long you’ll have translated quite a bit of the Scriptures yourself.

Read off (Slide)